New Delhi, December 25: If you drive long enough through parts of Rajasthan or southern Haryana, the Aravalli Hills almost disappear without you noticing. What should be rock and scrub turns into flat land, then a pit, then a road. For years, this has happened quietly. Locals noticed. Environmentalists complained. Courts intervened. Mining, somehow, carried on. This week feels different.

Over the last few days, the Union government has taken a set of decisions that, taken together, mark the sharpest attempt yet to stop further damage to the Aravalli Hills. On December 23, the Centre slammed the brakes on all new mining leases across the entire Aravalli range. Today, it followed that up with instructions that could push the protected boundary even further.

It is not a single announcement. It is a shift in posture.

A Range That Was Easy To Ignore

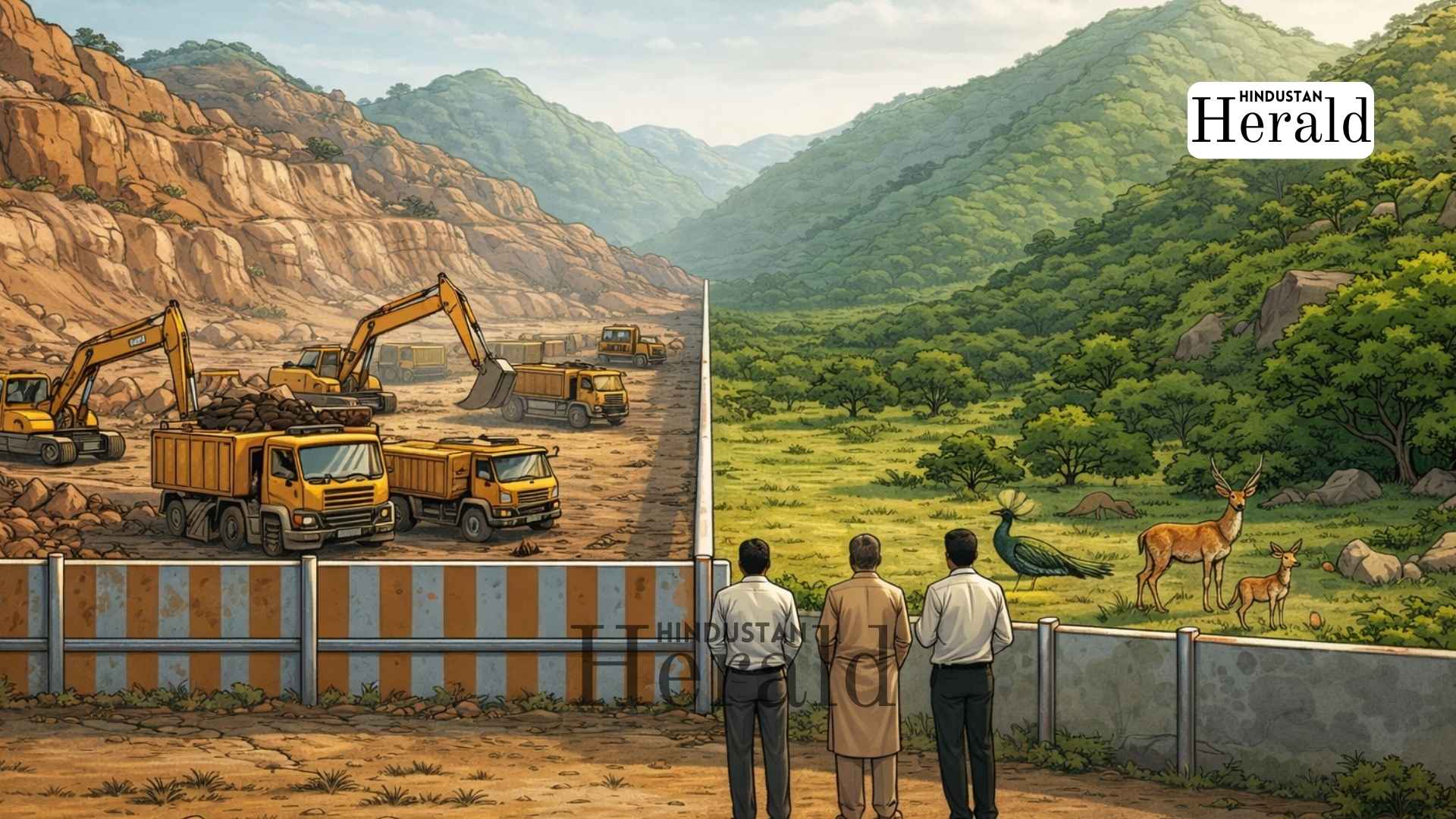

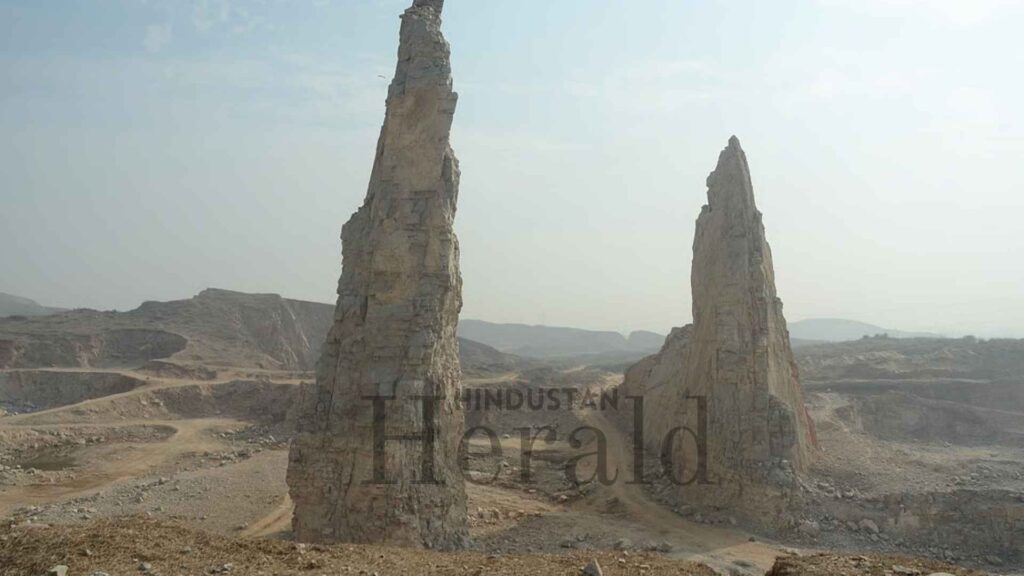

The Aravallis are old. Older than the Himalayas. Worn down, low-slung, often dismissed as hills rather than mountains. That has worked against them. They never inspired fear or reverence. They were simply there, and over time, they became useful.

Useful for stone. Useful for construction. Useful for revenue.

What often gets forgotten is what they quietly do. They hold groundwater in place. They slow down the desert. They soften the heat that would otherwise hit cities like Delhi and Gurugram even harder. When the Aravallis go, the damage does not arrive overnight. It creeps in through dry borewells, hotter summers, and dustier winds.

Mining has been central to that slow unraveling.

The December 23 Ban

On December 23, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change issued directions that left little wiggle room. No new mining leases will be granted anywhere in the Aravalli range, from Delhi to Gujarat.

According to reports in The Indian Express and Times of India, the ministry has deliberately rejected the old habit of treating the Aravallis as broken-up parcels governed by state lines. Instead, the range has been defined as a single geological system.

This matters. In the past, when one district tightened rules, mining simply popped up in the next. That game just got harder.

The ban does not shut existing mines automatically. That caveat has already sparked debate.

What About Mines That Already Exist

The Centre’s line is cautious but firm. Existing mines can continue only if they comply fully with environmental clearances and Supreme Court orders. States have been reminded that enforcement is not optional.

Alongside this, the government has put out a number that has surprised many. Only 0.19 percent of the Aravalli area is legally open to mining, a figure cited by NDTV. Everything else is already meant to be protected.

That statistic exposes the core problem. The issue has never been lack of regulation. It has been the ease with which rules are bent or ignored.

Today’s Letters To States

On December 25, the Environment Ministry pushed further. Letters sent to state governments outlined the next phase. More areas will be examined. More zones may be declared off-limits.

The work has been handed to the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, which has been asked to identify additional areas where mining should not be allowed at all. The criteria include ecological sensitivity, geological risk, and how the landscape fits together as a whole.

Officials familiar with the process say this is likely to expand the no-mining zones, not shrink them. Until that mapping is complete, states have been told not to change their mining policies in the Aravalli belt.

Reality Interrupts Policy

Almost on cue, reality intruded. On December 23, illegal mining near Alwar in Rajasthan was caught on camera. Excavators at work, stone being pulled out, reportedly from a prohibited zone. The footage spread quickly, and so did the frustration.

This is the part that no notification can fix on its own. Illegal mining in the Aravallis has survived court orders, raids, and public outrage before. It survives because penalties are weak, oversight is patchy, and local interests often look the other way.

Rajasthan officials have reportedly ordered inquiries. Similar inquiries have been ordered before.

The Supreme Court’s Long Memory

The Supreme Court of India has been here many times. Over the years, it has repeatedly described the Aravallis as ecologically sensitive and stepped in to curb mining and construction.

Legal experts say the Centre’s latest approach lines up more closely with the court’s toughest interpretations. Treating the Aravallis as one entity reduces the space for technical loopholes that once allowed mining to continue under different labels.

If states attempt to dilute these directions, the court is unlikely to stay silent.

States And The Uneasy Balance

For states like Rajasthan and Haryana, the pressure is real. Mining supports livelihoods in some districts. At the same time, water scarcity and extreme heat have made environmental damage impossible to brush aside.

As reported by The Economic Times, recent attempts by states to push for relaxed buffer norms, including around the 100-metre rule, ran into resistance from the Centre. The blanket ban effectively shuts that door, at least for now.

Where This Leaves The Aravallis

What happens next will not be decided in Delhi alone. It will play out in districts where trucks roll at night, and quarries sit behind tin fences. Mapping studies and policy letters matter. Enforcement matters more.

For now, the Centre has drawn a clearer line than it has in years. The Aravallis are no longer being treated as leftover land for extraction. They are being acknowledged as critical to water security, climate balance, and regional survival.

Whether that acknowledgement finally slows the damage is something the hills themselves will answer.

Stay ahead with Hindustan Herald — bringing you trusted news, sharp analysis, and stories that matter across Politics, Business, Technology, Sports, Entertainment, Lifestyle, and more.

Connect with us on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), LinkedIn, YouTube, and join our Telegram community @hindustanherald for real-time updates.

Covers Indian politics, governance, and policy developments with over a decade of experience in political reporting.