New Delhi, February 4: By evening, the Supreme Court corridors had emptied. Reporters moved on. Lawyers rushed to their next matters. Officially, there was nothing new to announce after the hearing involving West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee. No order was passed. No process was stopped. And yet, the day did not feel routine.

Something had shifted.

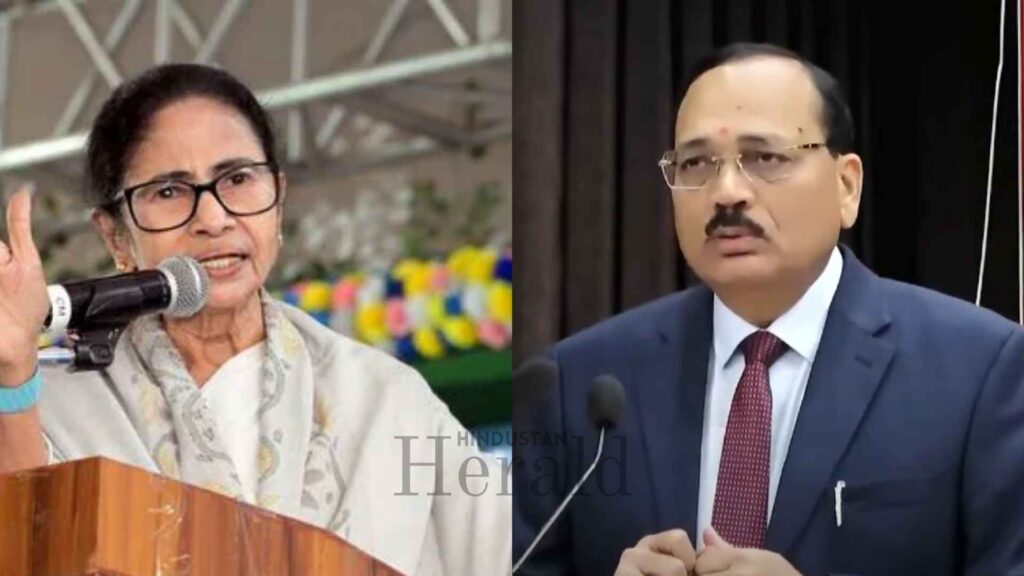

Earlier in the day, Banerjee had walked into the Supreme Court and done something almost unheard of in Indian politics. She stood up and argued her own case. Not through sound bites. Not through statements outside the gate. But directly, inside the courtroom, before the country’s highest judges.

A Chief Minister Steps Into The Arena

It is rare to see a sitting Chief Minister speak in court like an ordinary litigant. On Tuesday, Mamata Banerjee did exactly that.

Facing a bench led by Surya Kant, Banerjee spoke about what she believes is going wrong with the voter list revision in her state. Those present say she did not try to impress. She did not dramatise. She spoke plainly, sometimes almost like she was explaining things to people back home in Bengal.

Her worry, she said, was simple. Ordinary people were scared. Election workers were under pressure. And voters were being made to feel that their names could disappear from the rolls overnight.

What This SIR Fight Is Really About

At the centre of the case is the Special Intensive Revision, commonly called SIR. On paper, it is a technical exercise. Clean the voter list. Remove duplicate names. Update records.

The Election Commission of India says this is standard practice.

Banerjee told the court that what is happening on the ground feels anything but standard.

According to her, people are getting notices for the smallest things. A spelling error. A house number change. A name correction after marriage. She claimed these are being treated like serious violations, forcing voters to repeatedly prove their identity.

Her bigger concern was about micro-observers sent from outside West Bengal, many from BJP-ruled states. In her words, outsiders who do not understand local language, local movement, or local realities are being allowed to influence who stays on the voter list and who does not.

For someone standing in a courtroom, it sounded less like a legal argument and more like a warning.

The Moment That Changed The Mood In Court

The hearing took a serious turn when Banerjee spoke about deaths.

She claimed that the pressure linked to the SIR exercise had reportedly led to over 150 stress-related deaths, including one Booth Level Officer. The numbers have not yet been verified by the court, but the allegation landed heavily.

Election work in India is demanding even in normal times. Long hours. Constant scrutiny. Tight deadlines. Banerjee’s point was that this particular exercise had pushed people too far, creating fear instead of trust.

For a few moments, the courtroom fell quiet.

What The Supreme Court Chose To Do

The Supreme Court did not stop the voter revision process. That is the clear takeaway.

But the judges also did not brush aside the concerns. They called the issues “genuine” and issued notice to the Election Commission, asking it to respond by February 10.

One comment stood out. The bench suggested that if micro-observers are needed, the Commission could use Group B officers from within the state instead of relying on officials from outside. It was not an order. Still, such suggestions are rarely made casually.

Banerjee asked the court to ensure that no names are deleted until the case is fully heard and that existing voter lists be used if elections come up. The court did not agree to that, choosing to wait for the Commission’s reply.

So for now, the process continues.

Back In Kolkata, The Tone Hardens

After returning to Kolkata, Banerjee spoke more sharply. She accused the Election Commission of acting like a “WhatsApp Commission”, suggesting decisions were being taken casually, without proper checks.

The Trinamool Congress rallied behind her. Party leaders claimed that the SIR was quietly hitting their voters the hardest, especially in rural areas and minority neighbourhoods. Supporters flooded social media with clips of Banerjee’s court appearance, calling it a fight to protect voting rights.

The Bharatiya Janata Party hit back just as strongly. BJP leaders accused Banerjee of trying to protect fake voters and said voter list cleaning is necessary. They pointed out that the Supreme Court did not halt the exercise and called it proof that the Commission is acting lawfully.

The arguments, by then, had fully moved out of the courtroom and onto the streets and screens.

Why Many Are Watching This Case Closely

This case is not only about West Bengal.

Voter list revisions happen across India, often quietly. Most people only notice when their name is missing. If the Supreme Court lays down clearer rules after hearing this case, it could affect how such exercises are carried out in other states, too.

There is also a deeper issue. The Election Commission has long been seen as a neutral referee. When questions are raised about its functioning, even politically, it unsettles public confidence. The court now has to balance two things. Protect the system. And protect the voter.

All Eyes On February 10

For now, there is nothing more on record. The SIR continues. The Election Commission prepares its response. The court waits.

February 10 is the next key date. What the Commission says then could decide whether this case cools down or turns into a much larger battle over how elections are run.

Until then, the silence after Tuesday’s hearing feels uneasy. The kind of silence that suggests this story is far from over.

Stay ahead with Hindustan Herald — bringing you trusted news, sharp analysis, and stories that matter across Politics, Business, Technology, Sports, Entertainment, Lifestyle, and more.

Connect with us on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), LinkedIn, YouTube, and join our Telegram community @hindustanherald for real-time updates.

Covers Indian politics, governance, and policy developments with over a decade of experience in political reporting.