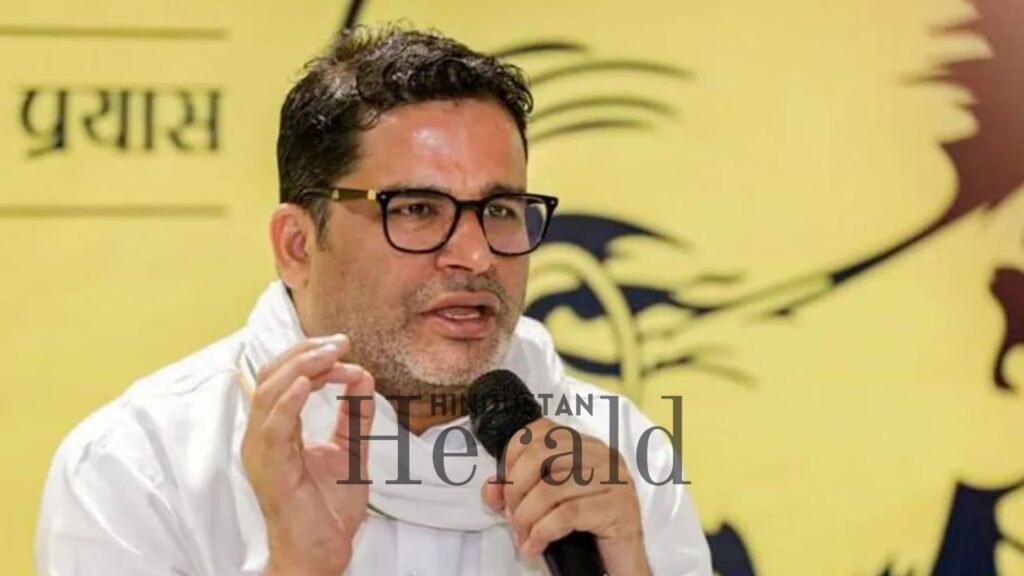

Patna, November 15: West Bengal’s tally was settled, Mamata Banerjee had the chair for a third time, and yet the politics on everyone’s lips was not the chief minister’s; it was the man who had engineered the campaign. Prashant Kishor has lived most of the last decade as a shadow force in Indian elections: the strategist, the fixer, the man whose spreadsheets and messaging moved parties from statehouses to New Delhi. Then he tried to become the story himself, and that is where the plot got messy.

Rise Of The Strategist

Prashant Kishor’s arc reads like an oddball Indian success story. From a village in Bihar to United Nations assignments abroad, he returned to find Indian politics hungry for professional campaign craft. He cut his teeth on governance and public health, then slid into campaign strategy after a stint writing for Narendra Modi during the Gujarat years. The early chapters are simple: analysis leads to ideas, ideas to a tight narrative, narrative to votes.

With the group that became I-PAC, Kishor helped package a message development, competence, and machine-like outreach, and it worked. Campaigns like Chai Par Charcha and Manthan became case studies in disciplined voter contact. Success followed: Gujarat in 2012, national victory in 2014. The man who once wrote speeches and policy papers was suddenly indispensable.

The Itch To Be More Than A Consultant

Here’s the thing. Being the brain behind a win is different from being the face of it. Kishor’s trajectory shows he never shrank from the idea of influence beyond strategy. He pushed ideas like lateral entry, urged more technocratic hires, and publicly flagged ethical lines. That occasionally put him at odds with political bosses. The rupture with Narendra Modi over lateral entry was the first fracture. Later, his association with Nitish Kumar matured into a partnership and a fallout that revealed a deeper reality: proximity to power is not the same as possession of it.

He moved from strategist to campaigner to would-be kingmaker and then to would-be leader. The Jan Swaraj campaign, a two-year village-level pilgrimage, an attempt to build audible grassroots traction, was his answer to the most basic critique: do you really understand voters, or do you only know how to reach them?

Where The Pilgrimage Stumbled

A pilgrimage across 5,000 villages is a bold gambit. Kishor insisted the campaign was about listening, about mapping local issues and returning with solutions. On paper, that checks every box for a new-ground political approach. In practice, the pilgrimage exposed two blind spots.

First, symbolism and narrative matter as much as the mechanics of outreach. Bihar’s political DNA is grafted to public movements, indignation politics, and long social narratives, land reforms, caste alignments, the Jayaprakash movement, and Champaran. A man known as the architect of others’ victory cannot simply transplant a Delhi playbook into Bihar and expect the same chemistry. His repeated statements that he did not believe in mass movements, and his preference for governance-by-expertise over agitation, read poorly in a state that prizes street energy and historic protest.

Second, message discipline slipped. Promises and positions that sounded clever in a consultant’s brief lifting alcohol restrictions “within 15 minutes” at the prospect of a Jan Swaraj government, turned into easy ammunition for rivals. Candidate selection added to the problem: the party fielded figures whose reputations undercut the “clean politics” claim. The result was a mismatch between brand promise and political reality.

The Public Moments That Backfired

A string of high-visibility episodes hardened a public perception that mattered at the ballot box. The Gandhi Maidan episode, the BPSC protests, the arrests, and the short, tense rallies, each incident layered on the last. A major rally that Kishor billed as half a million fell short on turnout and became shorthand for overreach. Critics pointed to it as evidence of weak ground control and inflated expectations.

When a campaign lives as much in optics as in organization, these moments don’t just dent morale; they reshape the narrative about leadership. Accusations against established politicians and administrative decisions can work when backed by a clear, sustained story of change. When those accusations arrive alongside contradictory messaging and uneven mobilization, they read as noise.

The Political Miscalculation

Kishor’s route from strategist to party-builder required not just tactical skill but social anchoring credible local alliances, patient cadre-building, and a sense that the project belonged to the community, not to a political consultant turned candidate. That anchoring was uneven.

There’s also an ideological gap. Bihar’s electorate responds to identity, redistribution, and social narratives as much as to governance metrics. When a campaign foregrounds managerial fixes and technocratic solutions without robust social framing, it risks being seen as out of touch. The Jan Swaraj experiment aimed to be different; in the election, it looked like a partial translation of other models into a context that demanded its own grammar.

What This Means Going Forward

Losing an election is not the same thing as losing a career. But the loss does force a reckoning. For Kishor, several practical choices present themselves. He can double down on organizational work, rebuild local networks, and reframe his narrative to address the social languages of Bihar. He can return to consulting, where his record is still remarkable, and keep political ambitions at arm’s length. Or he can attempt to learn from the missteps and craft a new political identity that blends his strengths with the messy realities of Indian grassroots politics.

Political life in India is rarely linear. Defeat has often been a prelude to reinvention. That said, the gap between command of campaign mechanics and command of people is real. Fixing it requires humility, time on the ground with the right partners, and a clearer sense of what the electorate wants to be told about its future.

The Unvarnished Take

Prashant Kishor changed how Indians fight elections. He professionalized message testing, data deployment, and micro-targeting. Those are now standard tools in the political toolbox. But the Jan Swaraj episode is a reminder that tools do not replace story. Voters respond to narratives that feel owned, not deployed; to leaders who seem lodged in local histories, not parachuted in with a consulting brief.

What this all means for Kishor personally is an open question. He is not out of the game by any stretch. But if he wants to be more than a brilliant operator, the hard work is not in the spreadsheet. It is in the long, often untidy work of building trust where it matters.

Stay ahead with Hindustan Herald — bringing you trusted news, sharp analysis, and stories that matter across Politics, Business, Technology, Sports, Entertainment, Lifestyle, and more.

Connect with us on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), LinkedIn, YouTube, and join our Telegram community @hindustanherald for real-time updates.

Covers Indian politics, governance, and policy developments with over a decade of experience in political reporting.