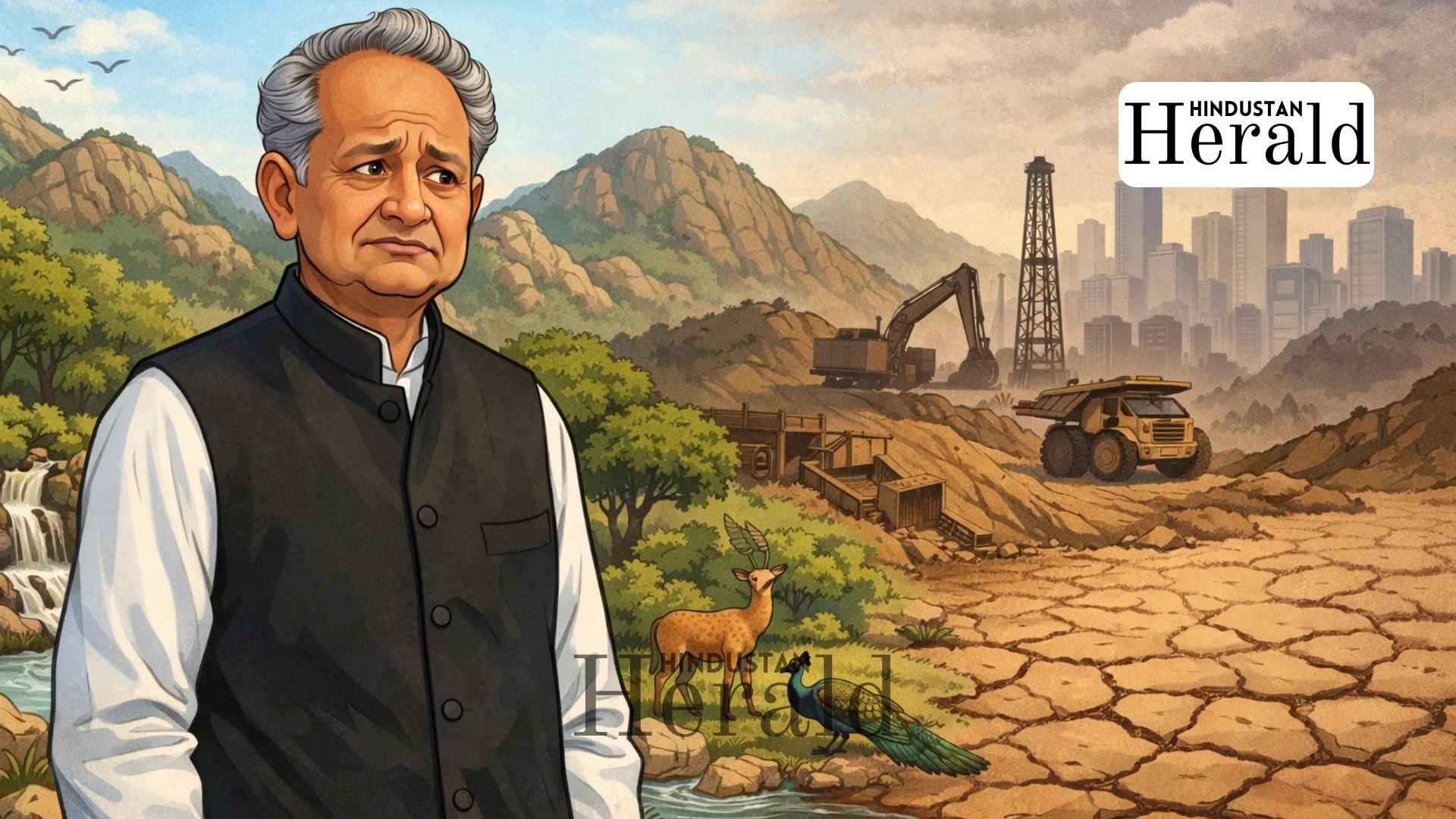

New Delhi, December 18: The Aravalli Hills have never asked for attention. They stretch quietly across Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi, and Gujarat, older than memory, older than politics. But this week, they were dragged back into the national spotlight, not by an earthquake or a flood, but by a file submitted to the Supreme Court of India.

On Thursday, the debate sharpened when Ashok Gehlot, former Rajasthan Chief Minister, publicly aligned himself with the Save Aravalli campaign. His language was unusually stark. The Union government’s position, he said, could strip protection from most of the range and leave it open to mining and construction.

That warning did not come from an activist group or a petition. It came from a senior politician who knows exactly how land policy works on the ground.

Why Gehlot’s Intervention Matters

Gehlot’s decision to change his social media profile picture in support of Save Aravalli was more than a symbolic gesture. According to Moneycontrol, he used the moment to press the Centre to reconsider the legal definition of the Aravalli Hills being presented in court.

In Indian politics, senior leaders rarely involve themselves so publicly unless they sense lasting consequences. This time, the concern is not limited to Rajasthan. The Aravallis influence water, weather, and air quality across northern India. Diluting their protection would not remain a local issue for long.

Still, the larger signal was political. Gehlot was effectively saying that what is being framed as a technical clarification is, in reality, a decision with irreversible environmental costs.

‘A Death Certificate for the Aravallis’

Earlier this week, Gehlot went a step further. Reacting to the Union government’s submission before the Supreme Court, he described it as a “death certificate for the Aravalli range”.

As reported by The Week, Gehlot warned that the Centre’s interpretation could remove protection from nearly 90 percent of the hills. The controversy revolves around a narrow but powerful criterion. Under the government’s definition, only land with a local relief exceeding 100 metres would qualify as Aravalli.

Environmental experts argue that this excludes vast stretches of low-lying hills, forest belts, and rocky outcrops that form the ecological spine of the range. These are precisely the areas most vulnerable to mining and urban expansion.

The Centre, for its part, has defended the definition as consistent with past records and legal interpretations. But critics say legality without ecological sense is a dangerous path.

What Gets Lost When Hills Are Reduced to Numbers

The Aravallis do not function like a row of peaks on a map. Their importance lies in what they do, not how tall they are. Reports highlighted by Navbharat Times underline that the range slows desertification, helps retain monsoon moisture, and supports groundwater recharge across large parts of Rajasthan and Haryana. Even shallow hill systems play a role in blocking hot desert winds and stabilising fragile soils.

If those systems lose protection, the impact will not be gradual. It will be abrupt. Falling water tables. Hotter summers. Dust storms that no policy paper can undo. As it turns out, many of the areas that protect Delhi-NCR from becoming climatically hostile fall below the proposed height threshold.

A Familiar Pattern of Mining Pressure

This is not new territory for the Aravallis. The Supreme Court has stepped in before. According to The Times of India, earlier court orders banned new mining leases in parts of the range after years of documented ecological damage. Existing leases were allowed to continue only under strict conditions.

Those decisions came after groundwater collapsed in mining belts and entire hills were flattened. Villages paid the price long before cities noticed. Still, pressure has never really gone away. Real estate expansion, infrastructure projects, and mining interests have continued to circle the range. Conservationists fear the new definition could reopen doors that were deliberately shut.

Water Stress Moves to the Centre of the Argument

Water is where the Aravalli debate becomes unavoidable. Recent reporting by Navbharat Times points to a wetland spanning nearly 5,000 acres within the Aravalli range that is now under threat from urban expansion. Such wetlands are not decorative features. They are part of a fragile system that keeps groundwater alive in an otherwise dry landscape.

Cities like Gurugram and Faridabad already face recurring water shortages. The Aravallis act as a natural recharge zone. Once damaged, that function does not return. Still, water security often remains a footnote in legal arguments that are often dominated by land records and definitions.

Wildlife That Refuses to Disappear Quietly

There is another side to the Aravallis that rarely enters courtrooms. Earlier this month, Navbharat Times reported the sighting of the world’s smallest wild cat in Mangar Bani, a forest patch within the range near Gurugram. The discovery surprised many who assume the region has already been stripped of wildlife.

Mangar Bani has long faced development pressure. The presence of rare species reinforces what conservationists have been saying for years. These hills are still alive. Many such habitats sit in areas that may no longer qualify as Aravalli under the Centre’s definition.

Citizens Step In Where Institutions Hesitate

The Save Aravalli campaign has grown steadily, driven largely by citizens rather than institutions. Residents across Delhi-NCR and Rajasthan have turned to petitions and social media to demand stronger protection.

On World Mountains Day, experts publicly criticised the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Aravalli definition, according to The Times of India. The message was consistent. Mountains cannot be protected by paperwork alone. Still, public pressure has limits without a clear judicial shift, activism risks becoming a record of warnings that went unheeded.

What the Court Is Really Being Asked to Decide

At its heart, this case is not just about hills. It is about how India understands environmental protection.

Is ecology defined by numbers on a survey map, or by the role land plays in sustaining life? Can development be planned without dismantling the systems that make cities habitable?

For Ashok Gehlot, the answer appears settled. For the Union government, administrative clarity seems to take precedence. For the Supreme Court, the decision will shape land use across multiple states for decades.

The Aravallis, meanwhile, remain unchanged. Old. Silent. Doing their work.

Whether the law continues to recognise that work is now an open question.

Stay ahead with Hindustan Herald — bringing you trusted news, sharp analysis, and stories that matter across Politics, Business, Technology, Sports, Entertainment, Lifestyle, and more.

Connect with us on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), LinkedIn, YouTube, and join our Telegram community @hindustanherald for real-time updates.

Covers Indian politics, governance, and policy developments with over a decade of experience in political reporting.