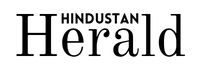

Kolkata, February 16: By 9 in the morning, the corridor outside a borough office in Kolkata was already packed. Young men in ironed shirts. Women holding clear plastic folders tight against their chests. A father filling out a form for his son, who stood quietly behind him. The shutters had not yet opened, but the line was steady, patient, almost stubborn.

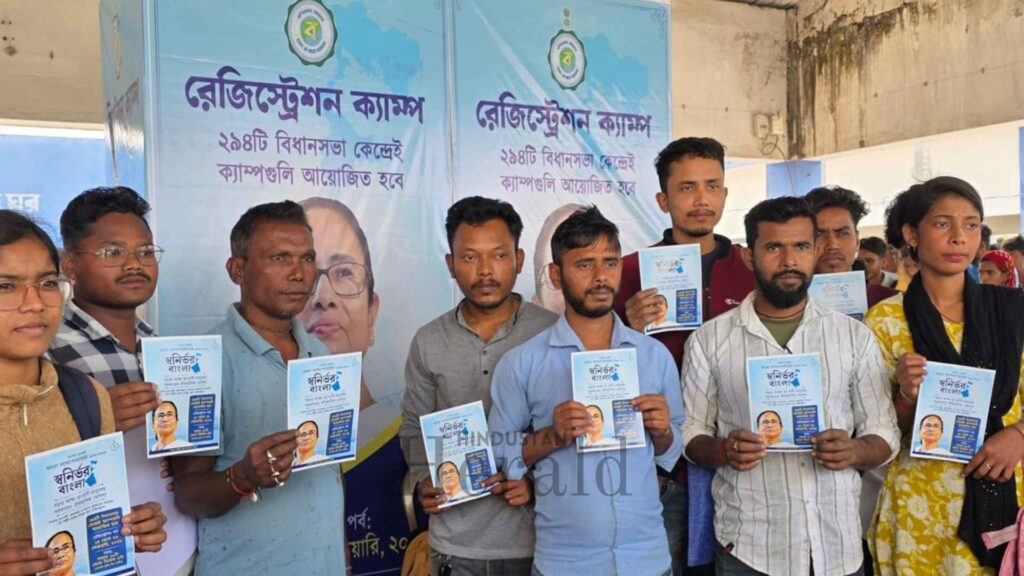

This is day two of Swanirbhar Bangla, the state government’s 12-day outreach drive that has suddenly become the biggest talking point across West Bengal. Officials say over 6 lakh applications came in on the first day alone. If the early rush on Monday is any sign, that number is only going to rise.

People are not turning up out of curiosity. They are coming because ₹1,500 a month can mean bus fare to an interview. It can mean coaching fees. It can mean not asking parents for money again.

A Stipend That Has Struck A Nerve

The scheme drawing the largest crowd is Banglar Yuva Sathi, aimed at unemployed youth aged 21 to 40 who have passed Madhyamik and are currently without a job. The promise is straightforward. ₹1,500 per month, credited directly to a bank account through Direct Benefit Transfer. The support can continue for up to five years or until employment is secured.

There is no complicated language in the form. No fine print that most people cannot understand. That simplicity may explain the turnout.

At one camp in south Kolkata, a 26-year-old graduate who has been preparing for competitive exams said he felt “seen for the first time in years.” He has been waiting for recruitment notifications, watching exam dates shift. The stipend, he admitted, will not change his life. But it will help him pay for travel and application fees without depending entirely on his family.

Across districts like Malda and Durgapur, similar scenes played out. In smaller towns, young applicants arrived early to avoid the afternoon heat. Some brought stools. Some brought water bottles. Many brought hope, mixed with doubt.

Eligibility requires permanent residence in West Bengal, a bank account linked to Aadhaar, proof of age and education, and passport-sized photographs. For many, gathering these documents was the first hurdle. Camps have set up help desks to fix minor mismatches in names or dates of birth. Officials insist they do not want technical errors to block genuine applicants.

Still, questions linger quietly in the queue. How long will approval take? Will everyone receive the money? What if funds fall short?

More Than One Scheme Under One Tent

Though Banglar Yuva Sathi dominates the conversation, Swanirbhar Bangla is not a single scheme. The camps function as a one-stop window for multiple welfare programmes.

Women have been lining up in large numbers to enrol in the expanded Lakshmir Bhandar scheme. Under the revised structure, women from the general category are eligible for ₹1,500 per month, while beneficiaries from the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities can receive ₹1,700 per month. For many households, this amount has already become a regular part of monthly budgeting.

Landless agricultural labourers are registering for annual assistance of ₹4,000, distributed in two instalments. Small farmers are applying for waivers on water taxes for government-operated tubewells. In rural belts, this has drawn a different kind of crowd, older, quieter, more accustomed to paperwork but equally anxious about approvals.

Bringing these schemes together in physical camps seems deliberate. Not everyone is comfortable with online portals. Not everyone has stable internet access. A physical desk with a government seal still carries weight, especially in semi urban and rural Bengal.

An official at a camp in Hooghly district said the administration had been instructed to minimise repeat visits. “If a document is missing, we try to resolve it here,” he said. “People should not have to come again and again.”

The Political Backdrop

Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has long relied on direct benefit schemes to anchor her government’s social policy. From student credit cards to cash transfers for women, welfare has been a consistent theme.

Opposition parties, however, have begun questioning the timing of this large-scale outreach. With political temperatures rarely low in the state, welfare announcements are often viewed through an electoral lens. The ruling party rejects that framing, saying economic stress among youth cannot wait for political convenience.

That debate is unlikely to fade soon. What is harder to dismiss is the visible demand. Six lakh applications in a single day cannot be manufactured. They represent real individuals who believe ₹1,500 is worth standing in line for hours.

Does ₹1,500 Make A Difference?

In pure economic terms, ₹1,500 is modest. It will not cover rent in most cities. It will not replace a salary. But for a job seeker who depends entirely on family income, it can cover transport, exam fees, internet recharge, or a short-term course.

Several economists have argued that small unconditional transfers provide psychological stability. When basic expenses are partly covered, job seekers may feel less pressured to accept low-paying work immediately and can instead continue preparing for better opportunities.

There is also the other side of the debate. Some critics worry that without parallel job creation, stipends risk becoming long-term substitutes rather than temporary support. Bengal’s youth unemployment challenge is not new. Recruitment delays in state departments and limited private sector expansion have fuelled frustration for years.

The government maintains that Banglar Yuva Sathi is not a replacement for employment drives. Officials describe it as interim support while skill development and industrial efforts continue.

Whether that balance holds will depend on outcomes over the next few years.

On The Ground, Real Stories

At a camp in north Kolkata, a young woman who completed her graduation in 2023 said she had applied for multiple private jobs but received no responses. Her father, a small shop owner, accompanied her. He handled the paperwork while she checked each detail twice.

In Malda, a group of friends arrived together, laughing nervously as they compared photographs and forms. One of them had forgotten a photocopy and rushed to a nearby shop. When he returned, breathless but smiling, the others teased him. The mood felt light, but beneath it was clear urgency.

There were also older applicants within the 40-year age limit who had lost contract jobs and were trying to restart. One man said he had been working on temporary assignments that dried up during the pandemic years. He called the stipend “not much, but something steady.”

The government has announced that disbursal for those registered during this drive will begin from April 1, 2026. That date is now circled in many minds. An acknowledgement slip in hand is reassuring, but money in the bank is what will build trust.

The Larger Question

Welfare politics in West Bengal is not new. What feels different this time is the sheer visibility of youth participation. These are not only rural beneficiaries. Urban graduates, diploma holders, and even postgraduates are lining up.

It reflects a broader anxiety about employment in a changing economy. Degrees no longer guarantee stability. Competitive exams are fewer and often delayed. Private sector jobs are concentrated in limited pockets.

In that context, Swanirbhar Bangla is not just a government programme. It has become a mirror reflecting economic uncertainty.

For now, the camps will continue until February 26, open from 10 am to 5 pm daily except on notified holidays. Files will be stamped. Forms will be uploaded. Data will be processed.

And every day, more young people will stand in line, documents pressed neatly together, waiting for a system to respond.

If payments begin on schedule in April, confidence in the programme will grow quickly. If there are delays, scepticism will rise just as fast.

Right now, what is visible is this: long queues, quiet conversations, tired officials, and a sense that something small but meaningful might change for thousands of households.

Sometimes, policy debates happen in television studios. This week, they are unfolding in municipal halls, school buildings, and block offices across West Bengal, one application at a time.

Stay ahead with Hindustan Herald — bringing you trusted news, sharp analysis, and stories that matter across Politics, Business, Technology, Sports, Entertainment, Lifestyle, and more.

Connect with us on Facebook, Instagram, X (Twitter), LinkedIn, YouTube, and join our Telegram community @hindustanherald for real-time updates.

Covers Indian politics, governance, and policy developments with over a decade of experience in political reporting.